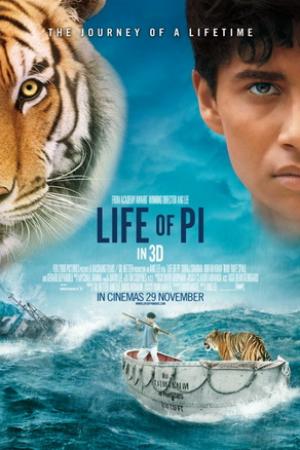

Life of Pi

Sunday, 23 December 2012 - Reviewed by

Life of Pi

Written by Yann Martel

Screenplay by David Magee

Directed by Ang Lee

Released on 21 November 2012 (USA)

Released in 2001, Yann Martel’s modern fable Life of Pi was a literary hit, winning the Man Booker Prize and the hearts of readers worldwide. It was, however, deemed by many impossible to translate to the screen. How could the sense of spirituality and adventure be brought to cinema? How could a story set almost entirely on a small lifeboat be made watchable? How would they get the tiger to do all that without eating the crew?

Step in Ang Lee, a talented director whose filmography, encompassing Brokeback Mountain, Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, and Hulk, can only be described as ‘eclectic’.

Sticking close to the novel, Lee frames the story through a visit to a middle aged Indian man named Pi (established Bollywood lead Irrfan Khan) by a writer (Rafe Spall, who’s now broken free of being merely "Timothy’s son" and has a pretty good career going for himself). The writer has been told that Pi has a story which will make him believe in God. "I cannot tell you what to believe," says Pi, "I can only tell you my story."

And so Pi embarks on telling his eponymous life, and it truly is a fantastical life. Raised in a zoo in Pondicherry, Pi was a spiritually greedy child, wanting to follow all the religions and coming into conflict with his scientifically minded father when he tried to see emotion in the eyes of tiger Richard Parker (named through a "clerical error"). Pi’s family are forced to move the zoo to Canada when faced with financial difficulties, but their ship is hit by a storm and Pi finds himself stranded in a lifeboat with an angry hyena, an unhappy orang-utan, an injured zebra, and his old acquaintance Richard Parker. It’s no big spoiler to say that three out of four of these animals don’t last long and the heart of the story is Pi’s relationship with Richard Parker as the two drift the Pacific together.

What keeps the film going during this long period of Pi’s isolation is the two main performances and the beautiful look of the film. Though newcomer Suraj Sharma, as the younger Pi, hasn’t yet mastered quieter, more reflective emotion, in the more active sequences he energetically captures the anger, the confusion, and finally, the determination that Pi goes through on his journey. As Richard Parker, and as a whole host of other creatures, the CGI in the film is remarkable. The film has a magical realist feel; nothing ever looks out of place, and Claudio Miranda’s cinematography brings the vast ocean to life with a series of gorgeous tableaux. Shots such as a bird’s eye view of the lifeboat as a whale passes below it were obviously devised with 3D in mind, not to mention the tiger jumping at the screen and the enormous horde of flying fish. For fans of 3D, it’s an experience to be immersed in, though for sceptics, it’s still an amazing looking film in two dimensions. I have to go off track slightly and mention the title sequence, a journey through the Indian zoo, bringing in flamingos, a hippo, one of those monkeys with the funny noses, and much more. The sequence is beautifully shot, with vibrant, lush colouring, and sums up the relaxed, spiritual ethos of the film.

This is a mindset that continues through Pi’s time on the boat, as, like at several points in his childhood, he takes the opportunity to connect with God. As an atheist, I would have personally liked a little less rumination on the nature of God and a little less of Pi’s stern belief that, whenever something remotely fortuitous happens, he is being saved by a divine being, but it is worth noting that the film does counter this with the scepticism of the writer and of Pi’s father. Also worth noting is the way the film deals with Pi’s relationship with nature – despite what you may foresee from Pi’s childhood experience with Richard Parker, the human-tiger relationship is never overly sentimentalised; Richard Parker is clearly a dangerous creature, there’s always a conflict going on, and Pi’s side of the relationship is most definitely concerned with not getting eaten. The tiger is vicious and entirely believable as a tiger, but through the careful storytelling and the way it highlights the beauty within that vicious nature, we end up caring for it anyway.

In the end, that’s what Life of Pi is about – storytelling. Pi’s story is a fable told through his recounting to the writer and, though I don’t want to give anything away, the final part of this framing dialogue rounds off the story in a way which made me reassess the rest of the film and, in fact, reduced some of my issues with the overly spiritual tone of the piece. It’s an intriguing ending which will make you question the nature of storytelling.

Life of Pi, to sum up, can be very spiritual at times, which may not be to some tastes, and, perhaps contrary to that, it ‘s not exactly cheery in its depiction of nature, but it makes that roughness of the world into a visually stunning film with a sad, iconic and elegantly told story at heart. It’s a treat for the senses and one to get you thinking.