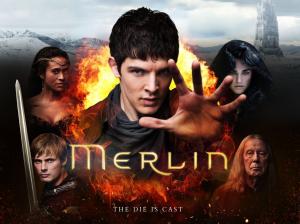

Merlin: Series Five

Saturday, 29 December 2012 - Reviewed by

Merlin Series 5

Written by Julian Jones (head writer)

Produced by Sara Hamill

Broadcast BBC One 6th October - 24 December 2012

Time and time again, we've heard those same words introduce each and every episode of Merlin, depicting the eponymous hero’s struggle with destiny and fate in the realms of Camelot. No one can deny that BBC1’s fantasy drama has proved a staggering rendition of the Arthurian legends of old ever since its début in 2008, but equally it would be impossible to deny the weight of expectations fans placed on the fifth and final season of the show this year. Could Julian Jones and his assembled production team ever truly satisfy the needs of this cult hit’s most avid followers?

Certainly, the signs weren't clear-cut in the opening stages of the run. For all its Game Of Thrones-riffing action and introductions of key elements of Arthurian lore (Mordred’s return a point of major interest), the opening two-parter Arthur’s Bane at times felt like a worrying rehash of stories gone by, recycling Kate McGrath’s portrayal of Morgana as a tired pantomime villain with little in the way of empathetic material. Before we knew it, Colin Morgan’s titular protagonist was portrayed in an unrealistic manner, goading Arthur to enforce the murder of a man only the warlock could know posed a greater threat in the long run. Thankfully, these suspicions and their implications on the character of Merlin became more compelling and believable as the season progressed, yet confined here they seemed vastly unfaithful to the legacy of the King’s greatest ally.

From here on out we moved into a number of standalone instalments that were met with mixed results and critical reception. The Death Song Of Uther Pendragon was little more than an unashamed rip-off of the horror movie genre, utilising predictable jump frights and spiritual hauntings to almost comic effect, so unbefitting were they of the show’s prior greatness. Another Sorrow was a slightly better yarn focusing on divisions of the realms surrounding Camelot, yet suffered from feeling like something of a non-event. Thank goodness, then, that The Disir came along to shake things up, placing a greater emphasis on the overall season’s narrative arc by placing Alexander Vlahos at the heart of the week’s mystery. Indeed, when Vlahos did step into the limelight for a fully-fledged performance as the man allegedly destined to kill Arthur, we as viewers could feel the colossal step up in episode quality as a result.

Angel Coulby had her time to shine as a budding British actress here, too: as fans had hoped, with The Dark Tower Coulby’s performing talents were showcased in great measure, with Gwen put to devastating psychological torture thanks to the schemes and manipulations of Morgana. Here, McGrath did come into her own, providing an emotive performance that was worlds apart from her character’s previous actions, and from here on out McGrath set a brilliant precedent which she did not fail to meet and match in the weeks that followed. The fall of Elyan in this sixth episode came as an unexpected surprise, and once again heightened the sense that no regular character was truly safe as the horns of war rang and the battle of Camlann beckoned.

After that successfully creepy romp, though, the season moved into what was by far its greatest failure. We've seen possessed opera singers, gaseous trolls and poorly implemented special effects aplenty in the five years that Merlin has graced our screens, yet few elements of the show have seemed quite as misjudged as the ill-fated 'Puppet Queen' trilogy. A Lesson In Vengeance, The Hollow Queen and With All My Heart were decent standalone instalments, yet only really served to have us question just why if the show’s producers knew this season would be their last, they did not trim the episode count down to a more feasible ten whereby they would not have to stretch out the narrative arc so much. By the time Colin Morgan had inhabited the guise of a female version of Merlin, it’s fair to say that the comedy of this tired trio of episodes had long worn off, regardless of the gravity and foreboding of ‘her’ departing words to the King.

The solution to this mid-season crisis? The tenth episode of the run, which carried a number of surprises and memorable moments. The Kindness Of Strangers presented an ambiguous Druid ally (portrayed wonderfully by Sorcha Cusack) who held a few choice words of wisdom for Merlin regarding his destiny, and while there was little of real substance to drive the season’s arc forward, it was a strong emotive tale. If fans needed an instance in which they could definitively assure the sceptics that this compelling series was worth a watch, then this adventure was definitely it- and the good times didn't end there...

Whenever a show wraps up, there are naturally going to be strengths and weaknesses involved within its final trilogy of episodes. Thankfully, for the most part The Drawing Of The Dark and The Diamond Of The Day didn't fail to impress, providing amongst Merlin’s most captivating performances yet. Colin Morgan and Bradley James mastered their roles as two of England’s most famous characters of lore, conflicted by the turn of Mordred (brought across brilliantly by Vlahos), then forced to separate in the midst of war, only to find themselves inevitably joined together again as the king faced his impending demise. The final moments we witnessed between these two iconic legendary incarnations were both touching and fan-pleasing, harking back to their first meeting and reversing the roles with the much-needed revelation of the magical secret that’s spurred the show on these past five years.

It’s probably fair to say that it was with the season finale The Diamond Of The Day Part 2 where things faltered just a little. It was still a relatively strong episode, packing many of the shocking twists that have made the programme such a joy to watch, yet its conclusion felt somewhat rushed. Character arcs weren’t always given a proper resolution (how will Gwen continue the line of succession, for instance?), and the supposedly innovative throw-forward to modern day England for a glimpse of Merlin’s eternal wait for the resurrection of Arthur’s legacy didn't quite hit the mark in the way it was intended. Even for a series that’s thrived on throwing in surprising twists on the lore of old, for me as a viewer this felt like a step too far, one attempt too many to play on our expectations. Then again, you’d have to wonder how the writers could ever have done things differently in terms of the climax without seeming over-indulgent or nostalgic.

Where does that leave the fifth and final season of Merlin, then? In short, while there are a good few missteps along the way, and it’s hard not to wonder why the episode count was trimmed down, it’s still a relatively consistent run. I wouldn't quite place it up with the best of 2012’s offerings- Sherlock Series Two and Doctor Who Series Seven Part One the greatest of Britain’s roster- yet there was still plenty enough reason to follow the show for its final twelve weeks. In a time of masses watching reality rubbish and a land of soap domination, it has been refreshing to see an indie drama rise up the ranks with such vigour and confidence over the course of half a decade, and with the broadcast of Merlin: The Diamond Of The Day Part 2, it's clear that BBC1's greatest fantasy saga has earned its place among the best of Britain's televisual history books.

The Best of Men

The Best of Men Bert & Dickie

Bert & Dickie Written and directed by Benedek Fliegauf

Written and directed by Benedek Fliegauf