Hollow Earth

Thursday, 2 February 2012 - Reviewed by Matt Hills

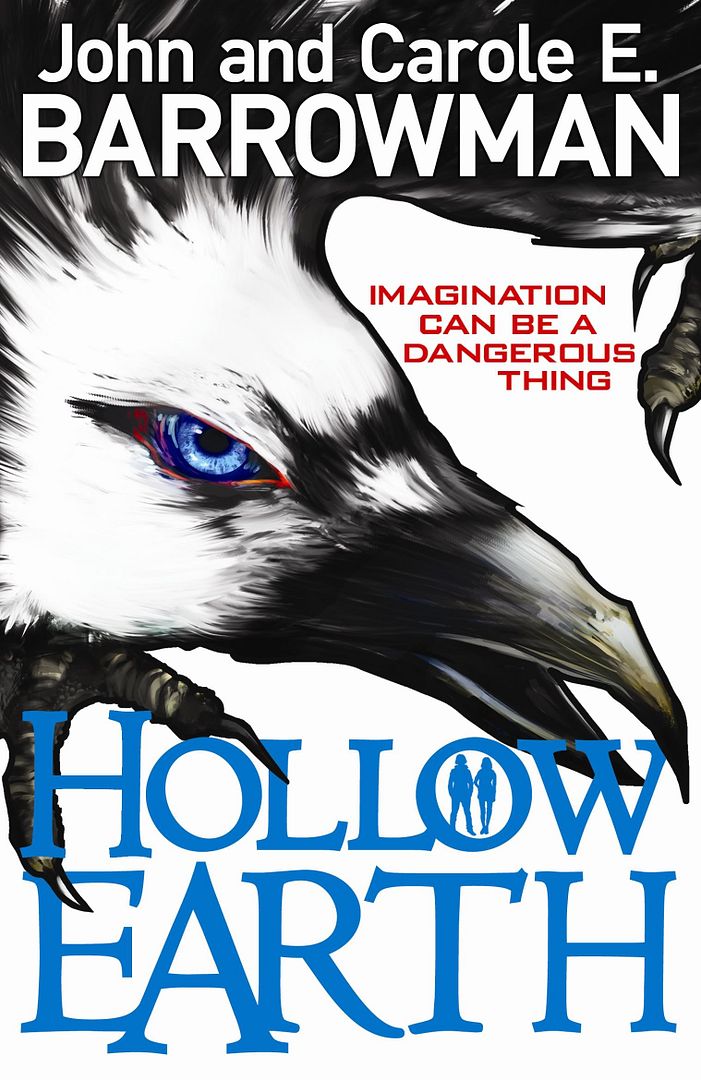

Hollow Earth written by John and Carole E. Barrowman

Hollow Earth written by John and Carole E. BarrowmanUK Release - 2 February 2012

Available to purchase from Amazon UK

Having collaborated before on a Torchwood comic strip and two volumes of autobiography, Hollow Earth marks the novel-writing debut of John and Carole E. Barrowman. Evidently drawing in part on their family background (and even including a mention of Selkies harking back to their Captain Jack story) Hollow Earth is largely set on the fictional Scottish isle of Auchinmurn. It's a 'YA' or Young Adult title – its lead characters are twelve year-old twins Matt and Emily Calder – but the book works just as well for older readers given its emphasis on art, imagination and old-fashioned adventure. Partly as a result of the storyline's focus on inspiring artworks, it's also a very visually-oriented tale that's easy to imagine becoming a film or TV adaptation as you encounter vividly described bursts of colour or accounts of CGI-style magic. Furthermore, each of the book's four parts is accompanied by a small graphic – reproduced above every chapter heading – which gives a pictorial clue to major events in that part of the story. And various real-world paintings are referred to, including works such as Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh (though Van Gogh's story is rather different to that told by Richard Curtis). At every turn, the image is paramount: words are used economically and emotively to paint bright pictures for the reader.

A central part of the tale deals with Matt and Emily's family history, and what happened to their absent father. The storyline also focuses on what special powers they have inherited as a result of their unusual parentage. Similarities to the abstract shape of Star Wars' narrative haven't passed the Barrowmans by, and Star Wars itself is name-checked at one point (p.141).

The novel's fantastical set-up concerns two powerful groups: the Animare, who can bring to life or “animate” works of art as well as their own dreams and fears, and the Guardians who are able to protect Animare and keep their powers safely under control. Matt and Em Calder are even more special than special, however: they are hybrids merging the powers of Animare and Guardian. This makes them uniquely threatening to the old order, and soon they're being hunted and watched by all sorts of interested parties.

John and Carole E. Barrowman convey a real love of art through this story, setting their conspiracies and neo-mythical events partly in the rarefied art world of London – the National Gallery offers one setting, for example. Quoting and appropriating the words of William Blake, Hollow Earth seeks to inform and educate readers at the same time as entertaining them with an old-school adventure romp. It reads like trad public service television rendered in novelistic form, and as such I think will feel remarkably comfortable to anyone who's ever been a fan of classic Doctor Who or the BBC's family serials. In terms of tone, it's miles away from the likes of Torchwood.

What's most impressive about this title, for me, is that it feels immediately like a fully-fledged fantasy world all of its own, made up of its own rules and values. Instead of a mystical “Force” the Animare's powers are distinctively centred on images and representations, and the novel finds all sorts of intriguing ways to work this fact into its narrative. Matt and Em are occasionally very fortunate to find drawing materials to hand, though the story's plotting also avoids moments of clunkiness by showing what happens when they are deprived of pens and paper and have to desperately improvise.

One major possibility buried within the novel's premise seems under-explored, though: what would happen to an Animare's work if it was mass-produced or mediated? If an Animare worked in television, would their TV shows have magical powers? Hollow Earth is content to restrict its living imagery to art and dreams, though Emily animates an image of her favourite vampire film character in one of her dreams, implying a fleeting, unnamed cameo for Robert Pattinson (p.106). Perhaps a follow-up will relate the world of Animares and Guardians to film/television production as well as painting, but for now the focus is very much on canvas rather than screen media – surprisingly, maybe, for a book likely to capitalise on John Barrowman's media stardom.

Hollow Earth succeeds in wrapping up its story well, but at the same time it leaves a key character mysteriously off-stage, engineering sequel possibilities. Also, we don't directly encounter all the different Guardians' Councils, creating further story-world gaps which could easily be returned to at a later date. And “Hollow Earth” itself remains somewhat tantalising; a place where all the monsters ever imagined are said to dwell. While preserving some of its mysteries, the book plays canny guessing games with readers by repeatedly introducing hooded or unknown figures and prompting speculation over who they might be...

The Barrowmans' favoured strategy is to suggest the importance and vitality of Great Art. A work of imagination about imagination, this could easily have become very tricksy indeed. Instead, it comes alive as a sincerely, skillfully written adventure story with an old-school feel and page-turning energy.